A lot of cool things have happened at Anfield in the last few years. The one I’ve been thinking about lately: the changing nature of the “playmaker.” Liverpool have modernized a dead concept.

Full disclosure: I have some confirmation bias here. I’ve disliked the notion of the “playmaker” for most of my life — probably since I stopped being good enough to be one as a teenager. I’m fairly sure I’ll lie on my deathbed one day and shout at someone, “stop applauding that stupid throughball!”

This comes in two parts:

Actual human-being playmakers usually create a “Racket of the 10” problem. In order for them to do their creative genius thing, they need certain parameters. Those parameters - less defensive presence, slower rotation of the ball, higher turnover rate - usually hurt the overall flow and performance of the team. Then, after the team slugs along, the group needs someone to bail them out. “Heeey, I’mmm heeeeree!” The playmaker has the most talent and is the one most likely to pull something out of nothing. Never mind the fact that the team probably wouldn’t have needed bailing out if they playmaker didn’t slow them down in the first place. It creates a self-assuring prophecy that the team needs the playmaker.

In every attack, you’re trying to maximize the probability of scoring (by playing the pass that sets up the best shot possible). At some point, you need to start a goal-dangerous action. You have to make the decision, What is the probability that Player X (with his/her abilities) can complete Pass Y to set up a shot, relative to other decisions?

We usually mis-assess those probabilities and try to make plays harder than they need to be, given that the majority of goals are scored by plays that do not require breathtaking talent. Whenever a player goes to do a hard thing on the soccer field - think, a killer pass - there’s usually an easier, higher-percentage - though less sexy - option.

We don’t put enough thought into the “relative to other decisions” part. The value of the pass isn’t just the pass itself, but what comes after it.

The main issue in today’s game with an attacking playmaker - the idea of a #10 sitting behind the strikers and dropping dimes - is that when those dimes don’t come off, and they don’t come off much more frequently than they do, then the play is dead — it’s a turnover that doesn’t lead to anything. It’s criminal at this point to force a turnover that doesn’t lead to anything.

We’re in the Golden Age of Turnovers. Turnovers have never been more useful. They might be, dare I say, even coveted to some. It’s possible to use turnovers well. Counterpressing, the act of pressing to win the ball back as soon as you lose it, has changed the game. Unfortunately, though, when the killer pass is made from an attacking position, the player at the endpoint is usually outnumbered and can’t counterpress.

Liverpool have changed that. Their two most “playmaker” players are their outside backs. Here’s a great rundown of numbers on right back Trent Alexander-Arnold that I copied from a ThisIsAnfield post from October, 2019:

By the numbers, his 128 progressive passes (best in the league), 3.36 expected assists per game (second best in the league), 7.02 crosses pg (most in the EPL), 11 total through balls (equal second in the EPL), 89 total long passes (equal second in the EPL), 92 passes into the final third (fourth in the EPL) and 16 deep completions (equal 12th in the EPL) demonstrate how well he’s performing.

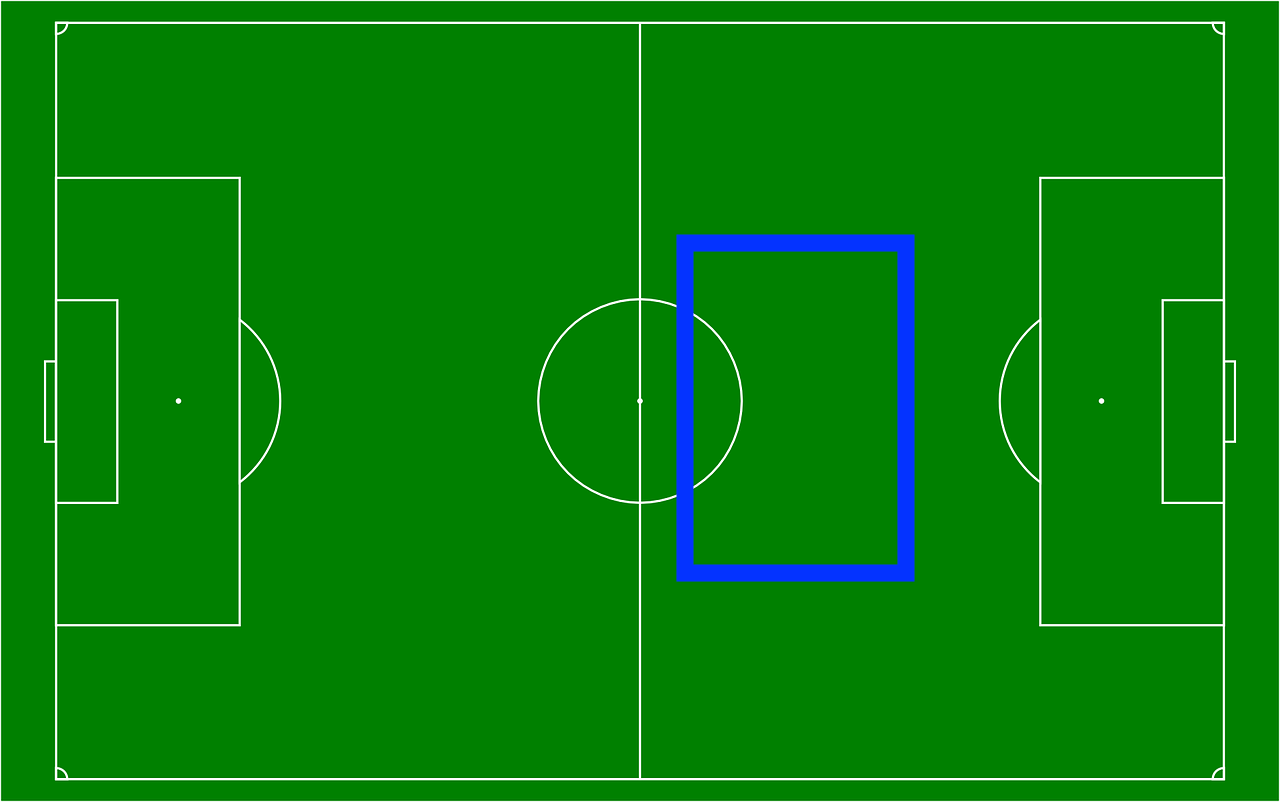

Liverpool ask their outside backs to take on the percentages that other teams expect from more attacking players. The key advantage of that: The number of players around the endpoint of the pass. When a defender makes the low-percentage huge-reward pass, he has six players in front of him. When an attacker makes a killer pass, it’s usually to a single onrushing player. More players around the ball = more players to counterpress. Every time Alexander-Arnold makes a killer pass, he’s also setting up a counterpressing moment. Every pass has a higher value because it includes itself and the subsequent counterpress. If the pass comes off, that’s great; if it doesn’t, that’s an advantageous scenario, too. It’s a win-win for Liverpool.

The idea of a deeper playmaker isn’t exactly new. Andrea Pirlo, of course, is the first to come to mind as a deep-lying midfielder. It seems to me, though, that the fundamental difference between “the Pirlo format” and “the Liverpool format” is that the Pirlo format is about the passer and the pass, while the Liverpool format is about playing with the larger ideology of being a “pressing team.” We’ve never thought of the playmaker as a cog within the larger scheme.

This gets highlighted by Liverpool’s structure in midfield. Since Liverpool use more creative, talented players at outside back, they get their sturdiness in the midfield. The outside backs play the killer passes, and the midfielders are there to win the ball back. The outside backs act as traditional playmakers, the artists with the ball, while the midfielders act as modern playmakers, the artists of the counterpress. It all fits together.

Beyond the tactical possibilities this opens, and perhaps the more important piece of all this, is the financial impact. Liverpool probably don’t care about this - I’m actually not sure that Klopp had a clear plan for any of this, rather than leaning into a budding revelation - but their outside back/center midfield structure is easier on the salary budget. Attacking midfielders are often the most expensive player on the team. If you can move their productivity to outside back, a much cheaper position, and insert a more industrious midfielder, a cheaper find in the market, then you’re shaving a decent change off your budget. In MLS, this switch would save a team, based on 2019 averages, roughly $1.5 million.

Liverpool have done a lot right in the last few years, and much is probably impossible to replicate for most teams. The idea of using deeper playmakers to add numbers to the counterpress, though, should be doable, especially for teams who need creative budget solutions.

That’s all today. Carry on (inside, please).